By Natalie York, Founder & Director of Research and Design, Flora Materials

Natalie York, Founder and Director of Research and Design at Flora Materials, suggests every architect and designer ask themselves these five questions to make more intentional, sustainable material choices. Read more for insights into these questions.

- What’s the carbon cost?

- What’s it made of?

- Where’s it made?

- How does it perform long-term?

- What’s its future?

Architects and designers are increasingly tasked with making sustainability a core part of their practice. Yet while energy systems and operational efficiency tend to dominate those conversations, the materials we specify are often considered secondary or the subject of value engineering for budget reasons.

The reality is that every specification, from flooring to wall panels to insulation, shapes not only a project’s aesthetics and durability but also its environmental footprint and long-term health outcomes. Materials carry embodied carbon, release toxins, and determine whether a building will stand the test of time or need costly replacement.

As both a former practicing architect and now the founder of a biomaterials startup, I’ve seen this challenge from both sides. Early in my career, I often found myself asking: Why don’t we have better options? Why do sustainability and performance so often feel like a tradeoff?

Today, thanks to advances in science and design, that compromise is beginning to disappear. The challenge now is learning how to evaluate these options with the same rigor we apply to cost, aesthetics and performance.

Here are five questions I believe every architect and designer should ask to make more intentional, sustainable material choices.

1. What’s the Carbon Cost?

Embodied carbon is the single biggest material-level metric, but you won’t usually find it spelled out in spec sheets. Instead, most brochures emphasize price points and finish options, leaving designers in the dark about a product’s true environmental impact.

Consider PVC flooring: estimates show it contributes nearly 10 million tons of CO₂ emissions annually, yet that number is nowhere on the label. When evaluating materials, consider both the up-front carbon from production and shipping and the longer-term footprint tied to maintenance, replacement, and disposal.

We’re often faced with difficult tradeoffs in the specifying process. Spray foam insulation, for example, delivers a high R-value per inch (essential in colder climates), but it’s made using petroleum-based chemicals. Bio-based alternatives like hemp wool insulation are emerging, but they can require thicker wall cavities or higher upfront costs. These compromises are frustrating because they force us to choose between sustainability and performance.

So how do we make more informed choices? As you evaluate products, ask whether the manufacturer provides an Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) or lifecycle analysis. Comparing bio-based options against fossil-fuel–derived ones often revealing significant carbon savings without aesthetic sacrifice.

2. What’s It Made Of?

Ingredients matter. Conventional products often contain toxic chemicals such as chlorine, phthalates, or VOCs, which can compromise indoor air quality and occupant well-being.

Over the past decade, cities and states have begun to formalize low-VOC requirements in their building codes. Fort Collins, Colorado, for example, now requires certified low-VOC products in certain construction applications, while Georgia recently passed regulations restricting VOC content in paints and varnishes. These moves, along with the rise of LEED-certified projects across the country, show how transparency in material health is moving from a voluntary choice to an industry expectation.

Even so, I often found myself unsatisfied as a practicing architect. Labels and certifications didn’t go far enough in revealing what was actually inside the products I was specifying.

Today, clients are pushing harder for that transparency. Certifications like Cradle to Cradle, Declare labels, or Health Product Declarations (HPDs) can help designers compare products on health and safety. But it’s also essential to understand what “green” terms really mean. The difference between biodegradable, compostable, and bio-based is significant and often misunderstood.

Procurement policies are also shifting in ways that underscore the urgency. Several U.S. states have introduced “Buy Clean” laws or embodied carbon requirements for public projects. These kinds of policies signal that material composition is now a front-line design decision, not a secondary consideration.

I’ve seen firsthand how frustrating greenwashing can be. That’s why Flora Materials is pursuing listing on the USDA’s BioPreferred catalog, which requires rigorous testing and a minimum of 91% bio-content in flooring. It’s one of the most reliable resources for sourcing credible bio-based products today.

And remember: bio-based does not just mean wood or stone. Advances are being made with tulip-derived resins, cellulose from pulp production, even corn grit from agricultural processing. The right fillers can transform waste streams into durable, functional inputs. Asking about composition isn’t a box-checking exercise—it’s a decision that directly influences human health.

3. Where’s It Made?

The “where” of a product is just as important as the “what.” Materials sourced and manufactured locally reduce shipping emissions, provide stronger quality control, and contribute to resilient supply chains.

The pandemic and subsequent shipping delays, tariffs, and global supply chain disruptions were a wake-up call. I experienced project delays firsthand because materials were tied up overseas. Those experiences reinforced how critical geography is, affecting sustainability, reliability, and cost all at once.

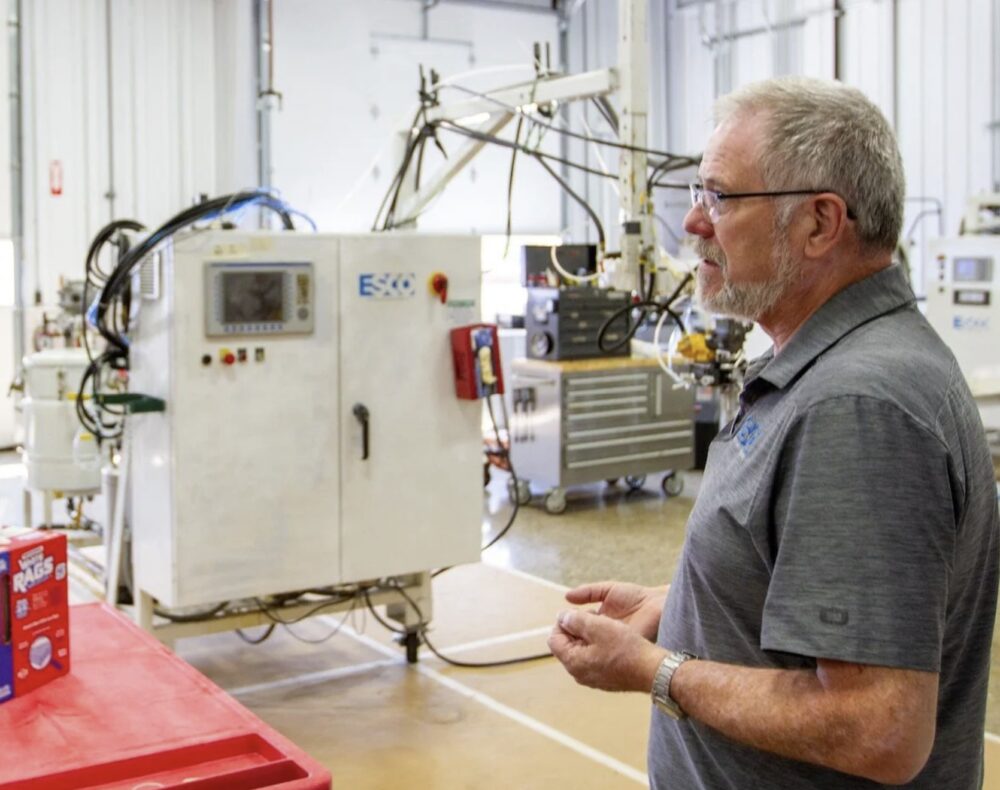

At Flora, we’ve made U.S.-based manufacturing a priority. The truth is that most large-scale material production has moved offshore. But we’ve found that existing domestic manufacturers are eager to innovate. By adapting their equipment to work with bio-based formulations, we’ve been able to breathe new life into facilities still operating here in the U.S.

Especially in the current tariff environment, it’s going to be increasingly important to talk to manufacturers about supply chain transparency. Where are the raw ingredients sourced? Where is the final product made? Sustainability is not just about the end product; it’s about the process that got it there.

4. How Does It Perform Long-Term?

A material isn’t sustainable if it fails after five years. Durability is central to responsible design. Historically, sustainable materials were perceived as less durable or more difficult to install—a bias that has slowed adoption. But that’s changing.

Today, architects should look for independent testing: ASTM standards, third-party durability studies, or USDA BioPreferred certification. These benchmarks matter because they provide confidence that a product can perform at scale.

At Flora, we’re working with the U.S. Army’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program to test our bio-based flooring tiles, a process that pushes them through some of the most demanding durability and performance benchmarks in the industry. If a material can meet military-grade durability requirements, it can perform extremely well in commercial and residential projects, too.

When I was practicing architecture, one of my biggest hesitations about specifying new products was whether they’d truly last. Today, I see durability as one of the strongest enablers of sustainability, rather than a barrier to it.

5. What’s Its Future?

End-of-life is as important as first life. As architects, we have a responsibility to ask: What happens to this material in 20, 30, or 50 years? Can it be recycled, composted, or safely broken down? Or will it end up in a landfill or incinerator, releasing harmful chemicals back into the environment?

Research shows that construction and demolition (C&D) waste accounted for 30–40% of the total solid waste stream globally in 2022. That means the majority of the materials we specify today are likely to become tomorrow’s waste burden unless we rethink their design.

The most forward-thinking manufacturers are designing for circularity—products that can be reclaimed, remade, or safely decomposed. Just as importantly, they’re designing platforms of materials, not just single-use products. A company building bio-based flooring today might expand into wall panels, acoustic insulation, or cladding tomorrow. That signals both innovation and longevity.

As a designer, I rarely had the luxury of thinking about a product’s end-of-life because budget and schedule pressures took priority. Now, as a material developer, I see how essential it is. If we’re serious about reducing waste and building a regenerative future, end-of-life must be part of the design conversation from the start.

Shaping the Next Standard Together

Architects and designers are the gatekeepers of material adoption. By consistently asking about carbon, composition, origin, performance, and future, we can move sustainability from niche to standard practice.

Bio-based materials are one of the most promising answers. But the real shift comes when we treat every specification as an opportunity to advance healthier, more resilient, and more inspiring places.

Still, it takes discipline to keep these priorities from slipping under the weight of deadlines and budgets. One of the most effective strategies is to define sustainability as a core value at the start of every project and to make that value visible (and valuable) to clients. When sustainability is built into the project’s guiding principles, rather than negotiated at the end, it becomes a shared standard that shapes decisions across the board.

It also helps to think strategically rather than universally. Not every product on a job needs to be the most innovative option, but every project has leverage points—places where a sustainable material can make the greatest impact, whether through insulation performance, lifecycle carbon, or human health outcomes. Identifying those opportunities early allows teams to invest where it matters most and balance cost elsewhere without sacrificing integrity.

Ultimately, making sustainability stick is about alignment and persistence. When your practice consistently champions these questions (even in small, incremental ways) they become second nature. Over time, that consistency shifts expectations, attracts like-minded clients, and builds a culture where responsible material choices are not the exception but the rule.

If I could give one piece of advice to my past architect self, it would be this: don’t accept compromise as the norm. The options may not always be perfect, but asking the right questions pushes the industry forward.

The future of design won’t just be defined by what we build. It will be defined by what we build with.