Italian-born, France-based architect Livio De Luca explains more about the integration of AI in architecture and his work on the restoration of the Notre Dame de Paris – scheduled to reopen on December 8, 2024.

Livio De Luca, a distinguished architect and researcher with a Ph.D. in Engineering and HDR in Computer Science, currently directs the Models and simulations for the Architecture and Cultural Heritage unit at CNRS. Recognized for his contributions at the intersection of architectural heritage and computer science, he has been honored with the Pierre Bézier Prize and the CNRS Medal of Innovation. His involvement in the restoration of Notre Dame de Paris reflects his commitment to using AI for cultural heritage preservation.

At last year’s SophI.A Summit, De Luca highlighted the significance of reality capture in heritage conservation and discussed the transformative potential of AI in architecture. He stressed the importance of professionals understanding and actively participating in AI development to maintain control over processes, especially in specialized fields like architecture and heritage. Delving into concrete examples, our conversation with De Luca explores the complexities of AI in architecture and its applications in the restoration of Notre Dame de Paris.

ArchiExpo e-Magazine: Can you tell us about your professional background?

Livio De Luca: I trained in Italy where I earned a classic degree in architecture which didn’t include working with Computer-Aided Design (CAD). I started working with computers for music, which heavily influences how I approach computer science and AI today. I began using sound sampling systems, which capture the ‘sound reality’ of an instrument, and also sequencers, computer-assisted music composition systems. Now, these two ingredients that I explored in music are found everywhere. It’s through the accumulation of instances, examples, images, 3D models of real objects that we can gradually build AI. I self-taught myself computer science in architecture during my architecture studies, and afterward, to specialize in computer science, I had two choices: attend a master’s program at MIT in Boston or at a laboratory in Marseille where I am today.

This laboratory was a French pioneer, a European leader in computer science applied to architecture, and was linked to the Media Lab in Boston. These two labs were working on the very first applications of CAD in architecture. Later, in 2013, with the Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, I co-organized the very first international congress on Digital Heritage which took place in Marseille, at the Mucem and the Villa Méditerranée. It was the first international conference on the topic of digital heritage.

ArchiExpo e-Magazine: What can you tell us about the SophI.A Summit?

Livio De Luca: SophI.A. Summit is linked to the establishment of artificial intelligence institutes in France, often led by Inria, a national institute for computer science and automation research. In the past, I had many interactions and scientific collaborations with Inria. From the outset of my work, I collaborated with a startup emerging from Inria, called REALVIZ, one of the first software applications enabling the reconstruction of 3D architectural scenes from photographs. This startup was later acquired by Autodesk.

Furthermore, with Inria, I developed a project called “Culture Free The Clouds,” which was an initial prototype of a cloud platform for the 3D creation of heritage and cultural objects. This collaboration was with Inria Sophia-Polis. Through this partnership, we continued to work in the field of AI for heritage preservation, my specialty.

ArchiExpo e-Magazine: What about the digital technologies used in the restoration of the Notre Dame de Paris?

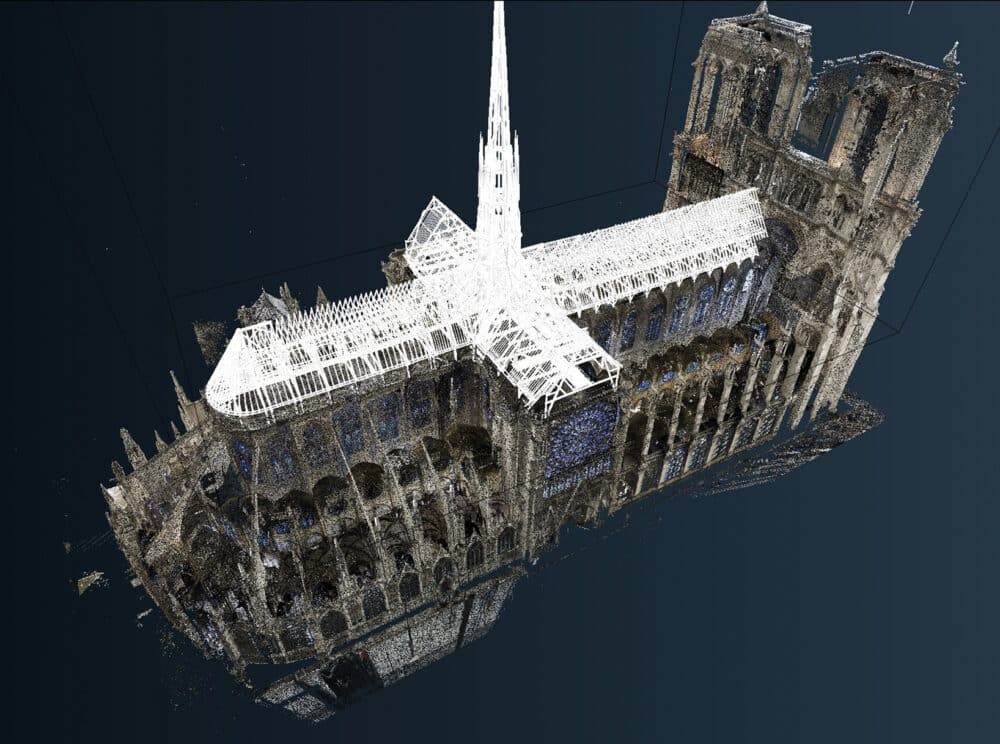

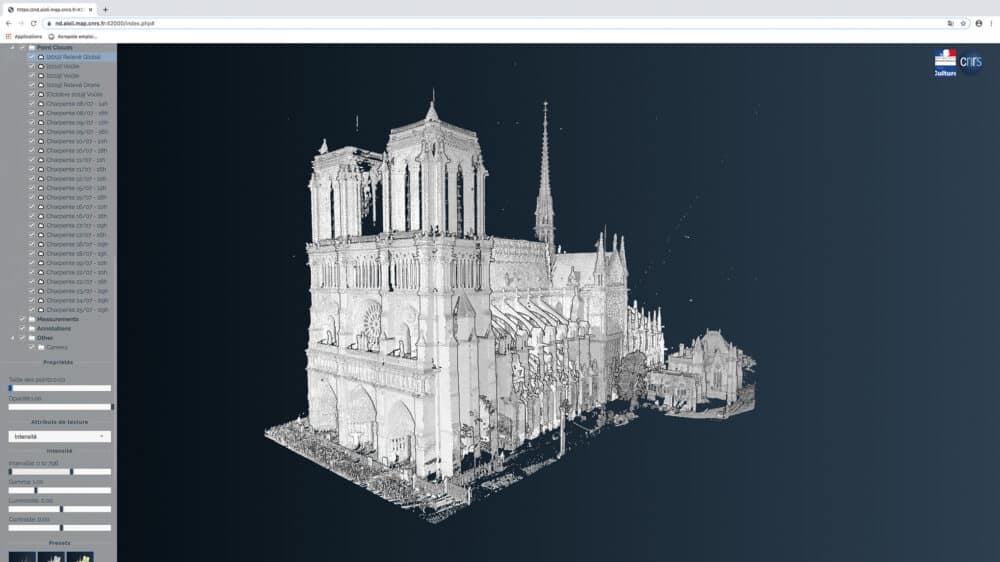

Livio De Luca: After the Notre Dame fire, there was significant mobilization of the scientific community, both in France and abroad. Several specialists wanted to offer expertise on issues related to materials, reconstruction of lost forms, archaeological inquiries, as well as structural or acoustic concerns. Thus, CNRS and the Ministry of Culture collaborated to establish a scientific initiative, which served as a scientific advisory board for the restoration process. This initiative aimed to manage the data from these sites and integrate them with the restoration project data. This became the focus of our intervention and the working group I coordinated since 2019, which later evolved into an ERC-funded project dedicated to developing a digital ecosystem for this operation.

The core idea is to link the physical characteristics of an object not only with the data representing them but also with the collective knowledge generated through the study of the object. This goes beyond the concept of a digital twin, as it involves representing knowledge from various disciplines around the object.

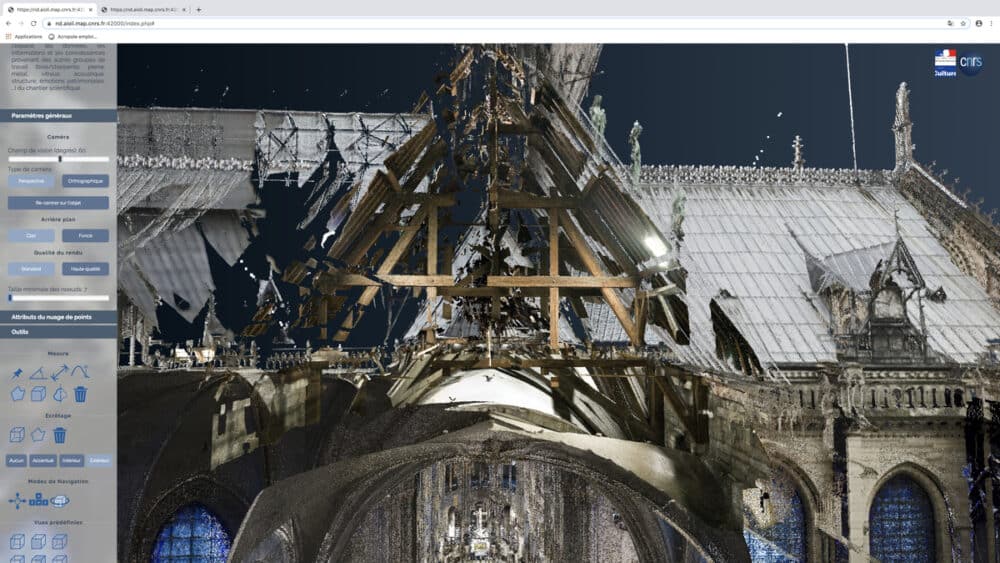

We develop methods to trace the paths professionals or scientists take from data production to analysis and interpretation to produce new knowledge. For example, imagine a group of archaeologists, architects, and engineers working on reconstructing an arch. They select elements, study the corpus, use digital tools for simulation, and validate simulation results for the reconstruction. We aim to record all contextual information at each step of the digital data produced. We do this by using a vast amount of data, including photographs, documents, drawings, and 3D models. We have developed a technological framework based on software tools that manage the entire lifecycle of digital data, from ingestion and categorization to semantic annotation and analysis, all accessible via web technologies to all stakeholders involved in the scientific endeavor.

To present concrete examples, we have a few based on iOli, an application developed in Marseille. It generates 3D representations from simple photographs and allows for annotation, facilitating diagnostics, such as the condition report, of the cathedral. This web interface enables the addition of annotations representing pathologies or information based on photographs.

VIDEO: #CurrentTopicsHS Lecture 10/2023: Towards cathedrals of digital data and multidisciplinary knowledge

ArchiExpo e-Magazine: Can you walk us through how this is used?

Livio De Luca: The photographs are related to the different parts of the building, but even if you see images, in reality, the application, which is based on cloud technologies, the application, behind it, generates three-dimensional representations related to annotations in space. You see simple images, but behind them, gradually, the application is projecting in 3D the annotations, and each annotated region is associated with a large amount of qualitative information. It’s as if we associate with all these projects, with all these photographs, the way we interpret both the state of health, the projected interventions, and all of these annotations being based on web technologies and always visible to multiple actors who can intervene, add, and so on.

Observations are very detailed in terms of inaccessible areas of the cathedral or areas that have been studied remotely. Today, the restoration project is in an extremely advanced state, and the date of December 8th has been chosen for the reopening. The deadlines will be met and the information provided will have been invaluable.

To exemplify the use of AI, we can take the question of finding the position and shape of an arch, the double arch, from the elements through an application of computer vision that we developed. The idea was to be able to finely reconstruct the geometry of the arch, to analyze the remains, the relics—these are the voussoirs you see on the ground [in the image shown during the interview]—, and to do so from photographs. The idea, a bit crazy at first, was to do a kind of spatio-temporal tracking of the voussoirs. The voussoirs were recovered after the collapse. The idea was to reconstruct the falling position of the voussoirs and then to digitize these voussoirs. And that’s what we did in this experiment.

We distributed thousands of photographs on which we were able to identify voussoirs that were on the ground. And so these photographs, we spatialized them, and as you can see in these images, there are Xs everywhere, these are the ground location positions of these voussoirs. This allowed us to associate voussoirs that we saw on the ground in these photographs, which had been taken at several temporal states, with the voussoirs preserved in the reserve. We built a robot that allowed us to digitize all these voussoirs. And here we see the level of detail, the richness of these voussoirs.

Subsequently, we were able to use the fine geometric information of the voussoirs to reconstruct the arch, thus giving valuable information to the architects about the layout, the exact geometry, and especially about certain constructive details of the oldest areas of the cathedral, especially from the 13th century.

Thanks to this work, we’ve provided a lot of information for the identical reconstruction of the site. But this information, today, we continue to feed it through the scientific study of relics. There is still much to know about the material, about the archaeological details, and about a whole host of information that interests scientists from various fields. This model, in a way, is a continuous enrichment that will continue to condense knowledge around the cathedral, around several states of the cathedral, knowledge around the study of relics. And of course, this knowledge will continue to enrich scientific research in heritage sciences, but this knowledge will also gradually serve as raw material to be exploited for artificial intelligence systems, for example, for studies that can be extended to other buildings.