More than 120 installations from 100 artists were on show across Saudi Arabia’s capital throughout November as part of the second annual Noor Riyadh festival – which continues with a museum exhibition until February.

The city was transformed into “a gallery without walls” by the expansive curation of Hervé Mikaeloff, Dorothy Di Stefano and Jumana Ghouth, who selected a broad variety of works, both spectacular and subtle.

Some of the most eye-catching pieces included “The Garden of Light” by Charles Sandison, who projected shimmering, shifting Arabic letters onto historical brick structures in the Diplomatic Quarter, and “Amplexus,” a tangled web of glowing red threads by Grimanesa Amorós, who drew inspiration from traditional Islamic architecture.

“The art being produced also has a dialog with the actual people who are living here, which is the most important thing,” said Neville Wakefield, a leading proponent of art outside institutional contexts, who curated the “From Spark To Spirit” exhibition in the JAX culture district. “If you’re not engaging the local audience, you’ve lost the battle,” he told ArchiExpo e-Magazine.

With the understated “Walking Lights” piece, Saudi artist Mohammed Alhamdan intended to do exactly that: He designed a system of street lamps that react to motion sensors, creating a surprising sensory experience for strollers on the Olaya Street thoroughfare, a new hub for pedestrian infrastructure in a city infamous for heavy traffic and long driving distances.

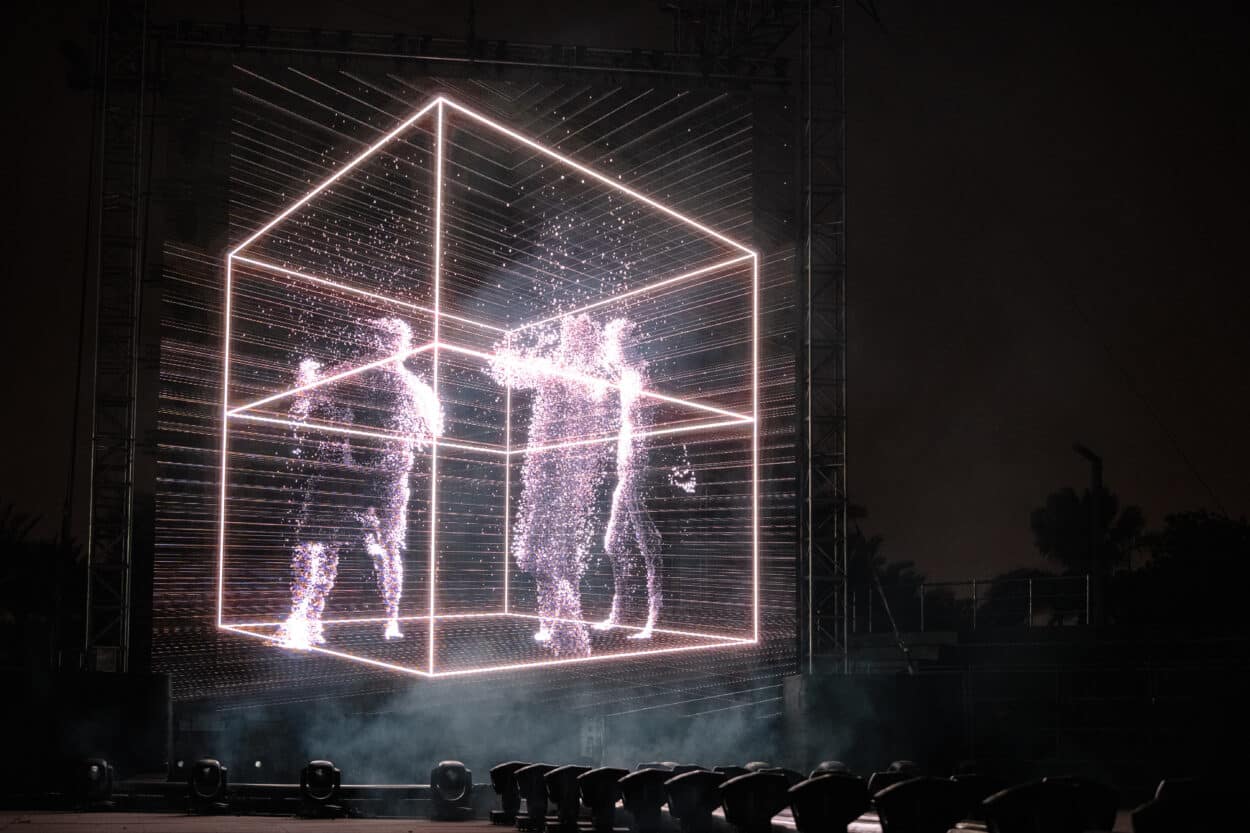

About 45 minutes by car from central Riyadh, two monumental installations dominated the night sky: “Oasis” by Arne Quinze is a crab-like sculpture that emits pulsing drone tones while psychedelic colors percolate around a 32x16m body crafted from LEDs and seemingly free-form metal shapes or textures; a short walk away, Christopher Bauder’s “Axion” invited visitors to explore outer space through the vessel of a light pyramid that represents a single particle of life.

Other festival sites included King Abdullah Park and the Wadi Hanifa, a sprawling 120km valley running through Riyadh, which hosted work by artists including Ahaad Alamoudi and Sabine Marcelis. In a country where the cultural sphere is still in early development, public art feels like a fitting way forward.

“The kind of western protocols that are so deeply ingrained in us – don’t touch, interact with the artwork at a distance – are not part of this culture,” explained Wakefield. “So it’s interesting to relearn that, rethink it, because that sanitized distance of a social barrier between the audience and the work doesn’t exist here.”