Murano glass, a once tightly-secured secret recipe, has evolved through the centuries. Watch our video to learn about Murano, a master glassmaker under the brand label Sogni Di Cristallo and new glassware by the daughters of Massimo Micheluzzi.

In 1291, Murano became the guardian of Venetian glass, the protector of creative secrets and the chain holding a tight grip on its master glassmakers. One could enter the world of glass on the islands that make up Murano but once you were in, you couldn’t get out. The years and centuries to follow saw the re-integration of more ancient methods, as traces of Venetian glass date to the 8th century, and brought to light new techniques. One crucial development was Cristallo or Venetian crystal in 1451 by Angelo Barovier.

Venice and the outside world bounced off one another. In fact, the creation of Venetian glass is attributed to close ties with the Middle East. When Bohemian glass entered the scene in the 1670s, the Venetian glass market suffered greatly until architect Giuseppe Briati retrieved the secrets behind the glass and adapted it to his own production. Following this, he invented chandeliers called “ciocche” with multiple crystal arms, decorated with festoons, leaves and multicolored flowers.

Although his invention was celebrated throughout Venice and recognized on the international level, he tried pushing his luck a little too far. He requested to return to the main islands of Venice, the Rialto islands, where he wanted to open his furnace factory. His wish was granted despite the law forbidding the activity of any glass furnace factory on the Rialto islands. Understandably jealous, the other glass masters threatened to kill Briati who, to save his life, proposed returning to Murano. Wish granted, again, and Briati reopened in Murano. Life continued, as did the evolution of Venetian glass.

READ: The history of glass in Murano and stay informed about the goings-on at the Museum of Glass.

Luckily, for our glass masters of today, times have changed. They’re no longer required to remain on the Murano islands. In fact, many of them have moved off the islands to the mainland; they’ve even gone beyond Mestre to the edge of the Venice region where they’ve opened their furnace factories in the countryside in order to offer a better lifestyle for their families. Still, the masters who aren’t on the islands use Murano glass and ancient techniques they’ve attained. The challenge of becoming a glass master has also remained intact and very few workers achieve this certification.

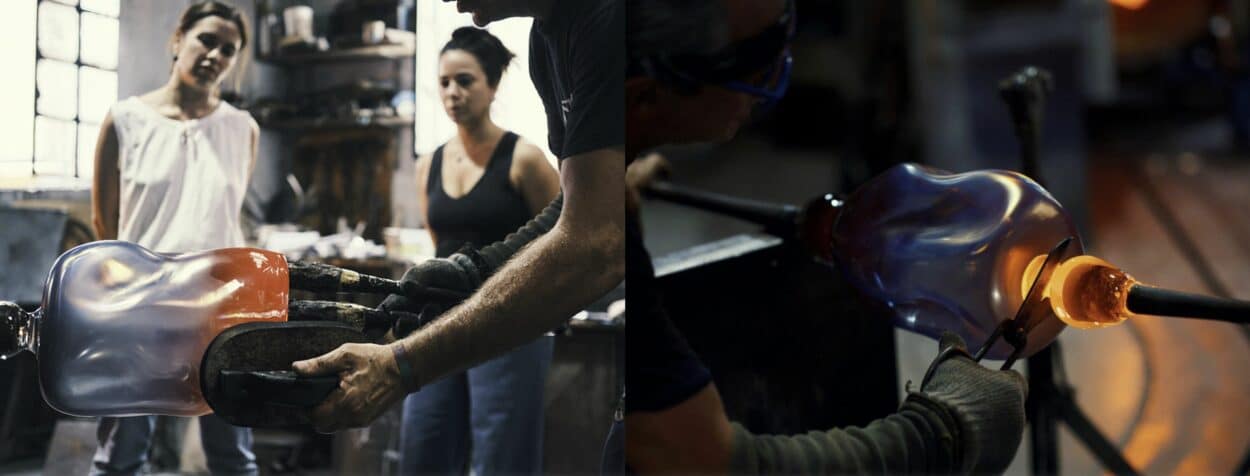

Marco Busato, a master glassmaker whose works are sold under the brand label Sogni Di Cristallo, explained during our visit to his factory, in the countryside, that a master will take two or three young apprentices under his wing but only one of them will later become master. Busato began when he was 8 years old, first by feeding fuel to the wood fire of the furnaces in 1943, a time when it was very normal for young children to work the furnaces. Later, he learned alongside his father, a master, who used chalk to mark foot placement on the floor in order to teach him where to stand and how to move during the process of making glass. He earned the title of a master at 18 years old, a very young age for anyone to gain this title, and followed in his father’s footsteps. They worked in Murano together until 1994 when they decided to open their own glass furnace where they specialized in chandeliers.

As per his Venetian roots and heritage of overcoming difficulties, Busato utilized the economic crisis of 2008 to invent a new idea for chandeliers. He integrated the light bulb inside the glass flower, hidden from the viewer’s eye, instead of implementing the traditional twist-on method. This latter concept required twisting the bulb onto an apparatus attached to the inside of the flower; yet, the bulb, bulky at the time, was visible beyond the glass form of the flower. Busato’s invention and creations brought him additional recognition and, since 2013, his work has been represented by the brand label Sogni Di Cristallo and selected for major international interior projects.

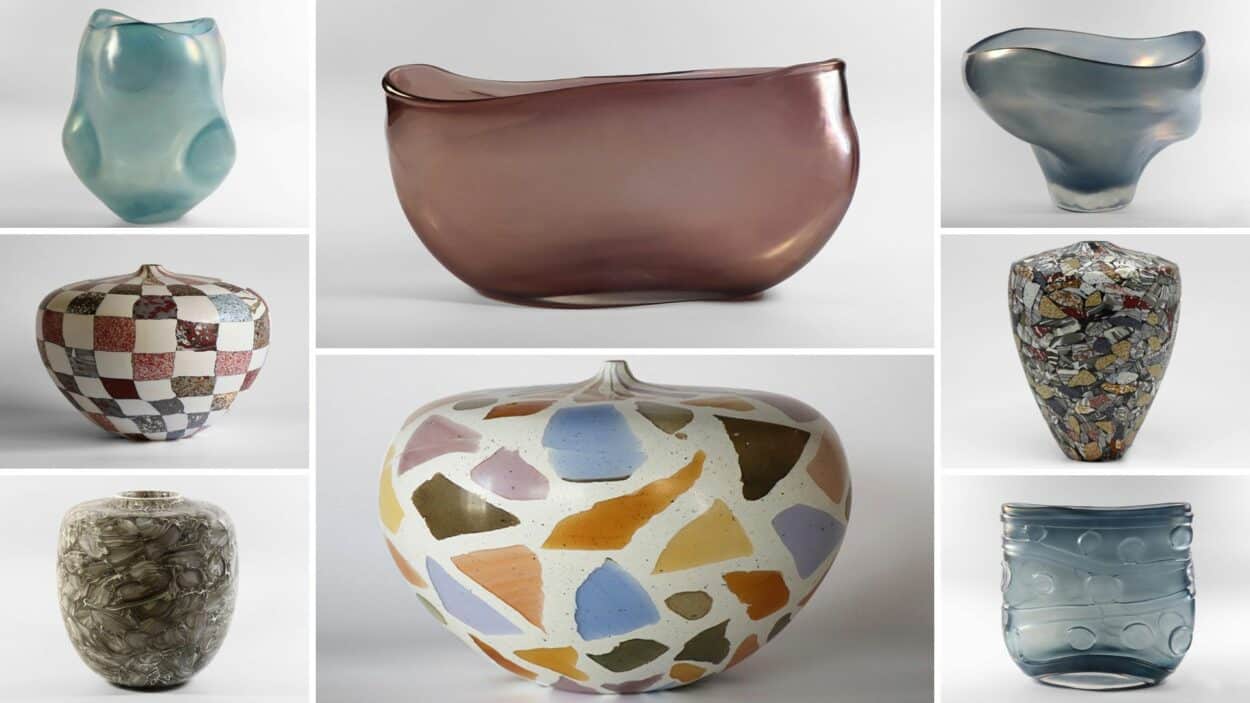

In parallel to the advancements of the Murano chandelier, artists and designers have been pushing glass masters to rethink how they use ancient techniques in modern ways. Venice-born Massimo Micheluzzi worked as a photographer for the Venini glass factory in his younger years, then later owned an antique shop on the Rialto islands before entering the world of glass. His glass designs can be split into two categories; the first is the result of using a bubble application done while blowing and a smoke technique, where the object is air rolled in smoke, and the second reveals intricate motifs. Serious research, of form and pattern, sits behind both styles which represent the history of glass as well as Venice itself. The smokey, bubble-like objects reference the water and air of the islands, while the patterns resemble what we might see on the streets.

When his two daughters suggested he create glassware in addition to his current pieces, he responded simply: “You do it.” And so they did. In 2019, having returned to Venice after nearly a decade of living abroad, Elena and Margherita Micheluzzi stepped into the family business by creating their brand Micheluzzi Glass. In the longstanding Micheluzzi shop, a beautiful display of their vases and glassware, magnetic to the eye, reels in strollers from the streets of Venice. In contrast to their father’s rather large-scale work, their pieces are dainty and of vibrantly mesmerizing colors. They work with the same glass master as their father, who employs the cold carving technique to achieve some of the girls’ designs.

The Micheluzzi family is an example of what we’ve noticed about Venice: Children of Venice often study the arts and leave to explore the world but they return, drawn to their birthplace, and when they return, they find a way to contribute to the growth of the city’s heritage, at times without realizing it. The strength of Venice as seen through its history has always been in the hands of its people and, despite the recent crisis of Covid and the Ukraine war, despite the closing of several factories last Christmas and, again, during the summer recently past, the energy in Venice contains an excited hope and sense of purpose.