January 2020—Participating in the Art Projects platform of this year’s London Art Fair, three talents explore the natural environment and the built world to generate reflection in their own way.

[Coming soon!] London Art Fair: January 22-26

Our three artists of the month arouse social, technical, philosophical and environmental questions. They examine our fragile relationship with the natural world, stimulating two underlying questions: What are the consequences of our interference with the natural world? How does personal perception of what we see affect how we define reality?

ArchiExpo e-Magazine spoke to all three artists to learn more.

The Brunt of Human Interference, a Vomiting Effect

In calm, scenic paintings of natural elements such as sticks, grass and vegetation, Canadian artist Judith Berry incorporates manufactured-like abstract forms that overtake our once organic landscapes in her oil paintings. Her works evoke concern for the environment and human impact but also how this interaction shapes our sense of place.

“I’m very concerned about the environment. However, my paintings are not directly related. While they are a reflection of the times and my concerns, they also reflect how I feel about landscape—what I consider to be the passage of time and history; narratives. We’ve manipulated the environment, but it reacts and often in a way out of our control. It’s unpredictable. Life is like that. We take action, an impact occurs, we adjust.”

Her paintings are about the shifting relationship between place and circumstance—and the ever-evolving surfaces that bear the brunt of human interference.

Her painting “Hello” forged a new way of painting for her, she said. The ropes are a way of encapsulating the ground and the air, creating form out of the atmosphere, all of which are made to appear malleable. Adding an element of hope, she said.

“Hope is found in a shared consciousness of the problem, which is no small thing. People act differently, discuss things differently and even vote differently.”

“Raising awareness is a form of hope. I don’t think painting is a concrete way to alter what we’re doing with the environment but, as public consciousness becomes more developed, we all become more concerned and things slowly shift.”

Her painting “Vomiting Figure” evolved organically, one form to the next, marking territories. When the figure began to appear and fire from its mouth destroyed the tree nearby, it didn’t make sense to her that the fire didn’t affect the figure itself. She repainted it.

“Fire comes from the mouth of the figure in a threatening way, destroying not only the tree beside it but itself as well. The self-immolating figure is examining its own actions, with a puzzled look cast on its burning hand, questioning where we invest our emotions, hopes, ambitions. Perhaps all this has been misdirected.”

It’s the idea of a figure undoing itself and the environment around it, of redirecting purpose and investment. The notion of undoing carried on to her later paintings. It was the beginning of the series she will present at the event in London. “Undone” is the title of one of the paintings in the series and, once again, portrays a deconstructing figure.

She is represented by Art Mûr. During the London Art Fair 2020, Art Mûr will feature a selection of Judith Berry’s recent paintings. In these, the landscape is fused with portraiture and still life.

Consuming Visual Culture—From Perception to Reality of Place

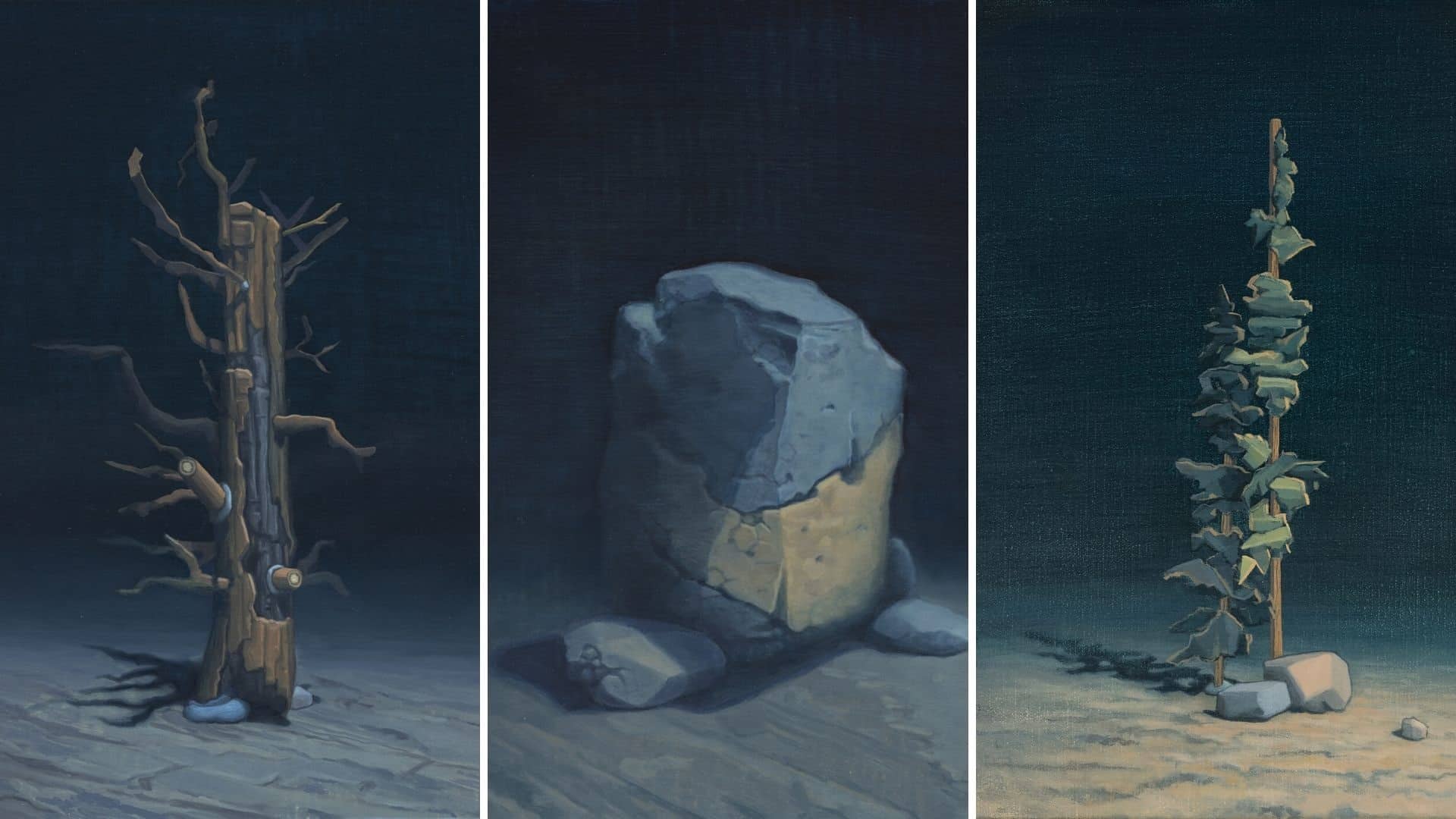

In order to stimulate a dialogue that explores the gaps between our perception and the reality of archetypal places, British artist Tom Down recreates landscapes as a series of lo-fi maquettes built in the studio and translates them into oil paintings.

“Building a physical model gives the painting a human feel.”

In the earlier days of his career, Down would used computer imaging to create his models. The physical models offer more details to work with, he said. Although Down focuses on elements of the traditional Romantic landscape—a lone tree, a pile of rocks, a patch of ground—, the aspects seen in his paintings are largely based on elements of nature found in film, television, video games, advertising, social media and iconic artworks.

“I grew up on TV and video games, where we see images through a filter or lens that create an idealized version.”

“Today, everything is seen through filters like on social media. We have a lot of fakeness, whether it’s how people present themselves in their holiday photos or how art itself has changed to better fit social media platforms for a different sort of aesthetics.”

“We seem to take it as a standard, as a reality, although we don’t see what’s going on behind the scenes. We’re in a weird territory now where we don’t know what’s authentic or real.”

His interest in fuzzy realities triggered the kind of paintings he aspires to create. From a distance, viewers see a landscape, but up close, viewers understand the element—the lone tree, for example—is made of cardboard. Closing the gap in distance between the viewer and the painting reveals the layers of reproduction.

Images: 1, Dolmen; 2, Empty Mountain; 3, Fallow Ground

Much of his conceptual inspiration also comes from iconic works of 19th-century European and North American painters such as Friedrich, Calame, Cappelen and Dalh. For the first time in his career, Tom Down has constructed large-scale models based on entire paintings.

By creating replicas with personal conceptual alterations of existing elements and exhibiting his art for the world to see, the artist investigates the question of how we view such images and the various modes of transmission, replication and alteration they’re now subject to.

Represented by Mint Art Gallery, the artist has assembled a solo exhibition with a larger-scale series of his works in addition to the smaller fragments. Tom Down is the 2018 winner of the Jackson’s Open Painting Prize and was in the shortlisted exhibitions for the 2019 Lynn Painter-Stainers Prize.

Truth and Illusion, Artifice and Nature, Interior and Landscape

British artist Suzanne Moxhay uses an archive of collected materials, then brings them together to create fictional environments in painting form. She plays with texture, surface, depth, space, scale, movement and architecture when constructing an image, pushing the viewer to question whether it is a real or fictitious place.

“When we watch a movie or look at an image, we’re absorbed into an artificial world that has been constructed. While engaged, however, it becomes reality. It’s not what we’d see in the world, only a manipulated version.”

“A photograph, for example, does not accurately record what you’ve seen or remember. If you look at a photograph of what’s been taken at a place where you’ve been, at the same time you were there, it doesn’t necessarily represent the memories you hold.”

Any form of representation we observe is a reconstruction of reality, according to Moxhay. The artist mixes and matches the various representations in order to create a space in which the viewer is “on the threshold of entering”, where they can contemplate.

“If there is human presence in the scene, it’s a different kind of experience. The viewer becomes a bystander, watching a story unfold. If the scene is empty, it becomes a setting for the viewer to contemplate the space and bring their own thoughts.”

Images: 1, Double; 2, Hothouse; 3, Rockery

Inspired by early techniques in cinema where painting, photography and model-making were combined to build a composite image on screen, she builds up the image in her studio using cutout fragments of source material and turns them into small stage sets on glass panels. After re-photographing the sets, she manipulates the images digitally, taking them further away from their original context.

“If you look at the prints [of my paintings], there’s a lot of disjunction. When looking closer at the image, you can see the different levels of focus, resolution.”

Her limited edition prints explore the boundaries between inside and outside, between nature and the artificial or man-made. However rich, textured, detailed, indulgent and lush these places are; they do not exist.

Represented by The Contemporary London, Moxhay will present large printed works and hand-painted photopolymer etchings at the event. Her past exhibitions include ‘GSK Contemporary: Earth Art of a Changing World’ and ‘Constructed Landscapes‘ at the Royal Academy of Arts, London and ‘Human Made Things‘ at Aspex Gallery, Portsmouth.