At this year’s fair, artists dismantled aesthetic, cultural, and ideological categories—inviting viewers to sit with ambiguity rather than certainty.

In a hurry? Here are the key takeaways:

- Many standout works blurred distinctions betweenWestern and non-Western traditions, craft and fine art, and past and present.

- Artists resisted ideological simplification,favoring hybridity, symbolism, and material complexity over overt messaging.

- Several exhibitions challenged viewers’ assumptionsnot only about art, but about knowledge, authority, and truth itself.

- The most compelling works demanded patience,ambiguity, and sustained attention in a polarized cultural moment.

The boundaries and hierarchies that have shaped much of fine art history, and that artists have increasingly sought to dismantle, were a recurring focus at this year’s Miami Art Basel. Across the fair, distinctions such as high versus low, Western versus non-Western, and fine art versus craft were repeatedly blurred or rendered irrelevant. This was evident in the dialogue between traditional Western motifs and indigenous or diasporic practices, as well as in works asserting non-Eurocentric cultural identities.

Throughout the exhibition, artists experimented with materials not typically seen together: tapestries and paintings embedded with silk, beads, and sand; sculptural assemblages of scrap metal and molten glass; and surfaces that emphasized texture as much as image. The result was a fair less concerned with purity of form than with hybridity, layering, and material intelligence.

Chinese Aesthetics in a New York Urban Context: Alisan Fine Arts

Opened in 2023, the New York branch of Hong Kong–based Alisan Fine Arts presented a focused exhibition of artists from the Chinese diaspora, a field in which the gallery has long specialized. The works on view drew on Western artistic methods while constructing distinctly contemporary Chinese aesthetics.

Across the presentation, meticulous craftsmanship and unusual surfaces reflected the hybrid Asian and Western techniques used in their making. Among the highlights were paintings by the late Walasse Ting, who spent much of his career in the West and collaborated with artists including Andy Warhol and Joan Mitchell. Ting’s vibrantly colored works, created with acrylic and Chinese ink on rice paper, depicted people and animals in flattened, abstracted forms. While the bold palettes recalled Matisse, the iconography and techniques remained distinctly Asian.

In The Allure of Fiery Red, a nude Asian woman holds a flowered fan across her body and another over her mouth, blending sensuality with restraint. I Think of You presents a more ethereal image: a woman’s enigmatic face emerging from a sea of flowers and color, suggestive of memory or lost intimacy.

Also featured was contemporary Chinese-American painter Kelly Wang, whose collages and paintings incorporate Chinese calligraphy and traditional practices alongside unconventional materials. In Cloud Dragon (2025), ink, dragon paper, mineral pigment, acrylic resin, and varnish form a celestial sphere that feels simultaneously elemental and constructed. The layered surface evokes something primordial—ambiguous, atmospheric, and resistant to easy interpretation.

On the occasion of Celebrating Friendship: Sam Francis and Walasse Ting (2021), Alisan Fine Arts produced a video that focuses on the life and works of diaspora artist Walasse Ting and the lifelong friendship with Sam Francis.

Mixing Genres and Techniques: Roberto Marquez

The art-world appetite for hybrid forms was also evident in the work of Mexican artist Roberto Marquez, exhibited by New York’s Palo Soto Gallery. Born in 1959, Marquez has painted for decades, though he achieved wider critical recognition only recently. His work has been described as rupturing the boundary between realism and surrealism.

Marquez’s paintings depict figures caught in states of terror, awe, or reverence within eerie, otherworldly landscapes. Thick layers of impasto give the works a sculptural dimension, heightening their emotional intensity. At Miami Art Basel, the gallery presented The Season of Insomnia, a four-painting series tracing cycles of death, life, and rebirth through landscapes marked by violent weather and exaggerated vegetation.In these scenes, alienated figures appear overwhelmed by their environments.

One painting, (As Far as Memory) Winter, shows a bare-chested man kneeling amid a forest of cacti, arms outstretched in apparent supplication. Accompanying texts note Marquez’s engagement with Mexican retablos, medieval European art, and Renaissance religious painting. The power of these works lies in how such influences are fused into a new symbolic language—one that can be read as a meditation on climate anxiety or a post-apocalyptic future, without collapsing into didacticism.

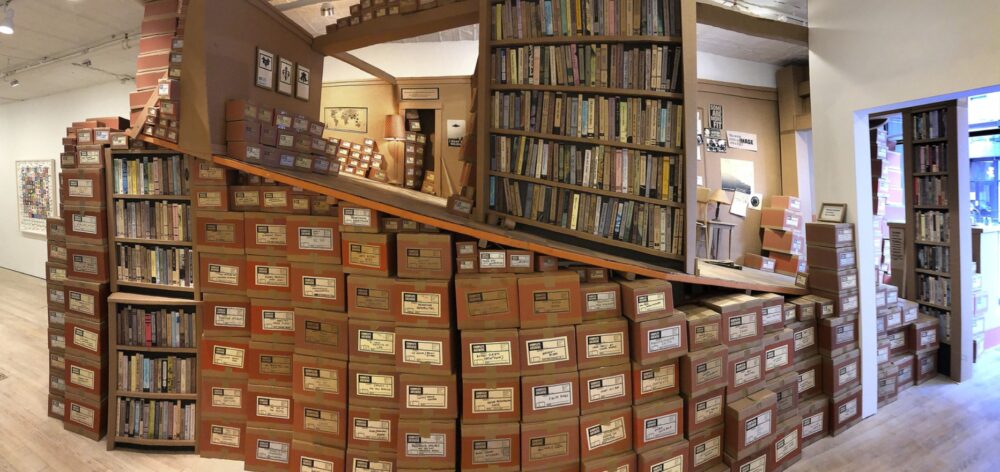

The Last Library IV: Written in Water

In the Meridians section—dedicated to large-scale works that challenge the traditional art fair format—New York gallery Freight + Volume exhibited The Last Library IV: Written in Water (2020–2025) by Ward Shelly and Douglas Paulson. This room-sized installation, constructed from paper, ink, and wood, encloses a surreal, slanted corridor leading into a classroom. On the blackboard, a phrase is scrawled:“Truth is a Puppet Show: there are always puppeteers.”

Shelves lining the space overflow with fake books that were never written, bearing titles such as You’re a Sucker: Washing the Feet of Others, 100 People Worse Off Than You by “Ivanna Trump,” and We Cannot Win by former U.S. Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz. Overhead, boxes of mock “secret documents” are labeled with categories like “Mind Control Preferences” and “Suggesting Fear,” alongside diagrams purporting to reveal hidden patterns guiding history toward dystopia.

The installation evokes George Orwell’s 1984, suggesting not only a collapse of scientific understanding but a broader erosion of shared reality in a post-truth age. Shelly described the work as a meditation on the declining influence of the written word.

“We are coming from a print-based world,” he said, “but we are headed into a new world where we don’t understand things. Can we have facts without the written word—without truth?”

Reconsidering Assumptions

Across these presentations, the most striking quality was not merely the breakdown of aesthetic hierarchies, but the way the works unsettled viewers’ habits of categorization more broadly. Many resisted easy moral or ideological sorting, the very kind of sorting that dominates contemporary discourse. Rather than reinforcing binaries such as Western versus non-Western or tradition versus innovation, the works exposed how provisional and constructed such frameworks can be.

The artists at Alisan Fine Arts, for instance, challenged the assumption that cultural identity must align with either nationalist authenticity or Western assimilation. Marquez’s paintings complicated the impulse to read art primarily as political messaging. The fake books, pseudo-documents, and paranoid diagrams in The Last Library point not only to propaganda machines on the political right or left, but implicate viewers in their own desire for explanatory certainty. It suggests the problem is not simply misinformation, but our collective dependence on narratives—any narratives—that promise moral clarity and intellectual comfort.

Taken together, these works suggested that what may loosen the grip of polarized thinking is not better slogans, but a renewed tolerance for ambiguity and sustained attention. Rather than reassuring viewers of their moral superiority or confirming ideological loyalties, the strongest pieces at this year’s Miami Art Basel provoke discomfort, uncertainty, and self-reflection. In a cultural moment defined by certainty and accusation, the refusal to simplify—whether formally, culturally, or intellectually—may be the most radical gesture of all.