Artist and art historian discuss the topic of writing history now through art, memory, and the shaping of the present in a discussion at Art Basel Miami.

History seems, definitionally, to be relegated to what has already occurred—it is the past, centuries, decades, or in some cases, only months. During a talk at Art Basel Miami, Artist Hank Willis Thomas and art historian and archivist Anne Helmreich insisted on viewing history as it forms in front of us. Through the talk, “Writing history now: Art, memory, and the shaping of the present,” they wanted us to recognize the historicity of the present. The fact that what happens today will, someday, become history. It means what is happening today is already, in a sense, historical. That a moment never passes that does not participate in history.

Moderated by Sandra Jackson-Dumont, the talk had a didactic edge. They advocated for recognizing history in terms of the history-of-now and the history that has passed, as well as having a critical engagement with narratives, facts, and memories. For them, history should not be taken for granted or understood only passively, where one accepts the default narrative. The function of art, especially for Thomas, wasto activate a critical re-framing of history.

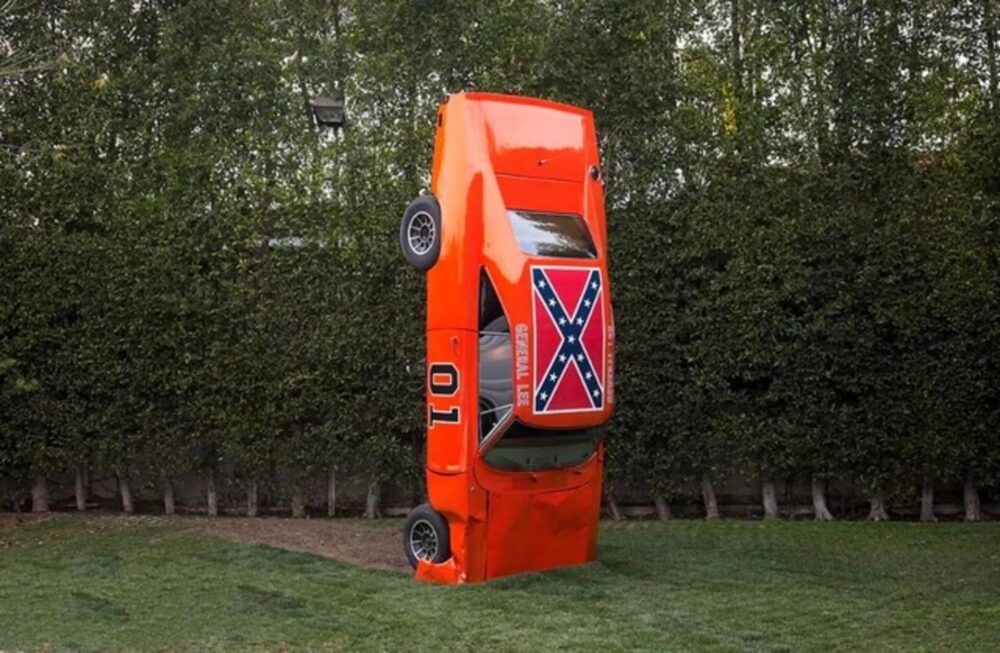

One of the pieces that was not in the Basel, instead circulating on the PowerPoint behind the stage, was a photo of an installation by Thomas titled, A Suspension of Hostilities. The piece is the instantly recognizable car from the American television show, The Dukes of Hazzard (which he said he grew up watching and re-examined later in life). The car is standing vertically, hood-first, the top of the car featuring an image of a Confederate flag. Here, we see, illustrated visually, the confrontation that Thomas thinks is necessary.

Beyond the Individual: Collective Stories

At the start of the talk, Thomas began by noting that he is not interested only in individual stories. Instead, he is invested in collective histories. Rather than making art that revolves around “history,” which invokes an individual viewpoint, normally at the exclusion of others, Thomas said he was fascinated by “our stories.” Thomas was concerned with the way some stories can position themselves as universal, effacing other stories.

Art is, of course, a mixture of individual experiences and social or collective narratives, but some artwork from Art Basel Miami seemed to precisely capture these collective narratives.

Mickalene Thomas’ piece, Resist #10 at the Levy Gorvy Dayan gallery booth, exhibited this exact quality of a collective history. The piece featured a montage of individual moments from the civil rights movement, bordered by rhinestones and occasional bits of text, such as “Black Lives” and “people.” There was clear continuity between this piece and the storytelling that Thomas advocated for: It showed individual moments of a historical struggle, such as a Black woman from the mid-20th century, crying, and a Black person being choked by what appears to be a police officer.

A clear theme of witnessing a collective history of suffering suffuses the painting: an eyeball, made of rhinestone, is superimposed in different areas throughout the piece.

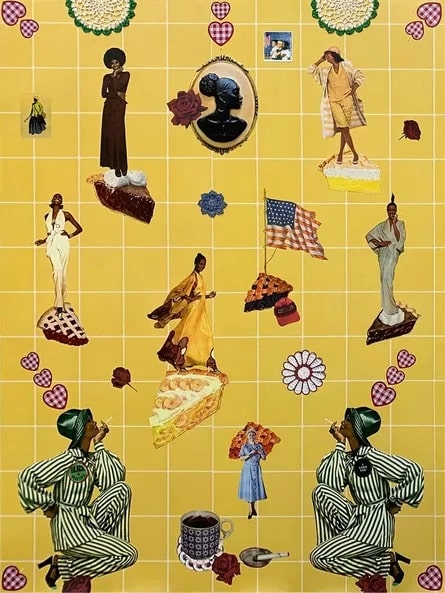

In a similar vein, but tonally distinct, Genevieve Gaignard’s mixed-media collage, Any Way You Slice It, also presents collective stories. The piece features slices of pie, American flags, cigarettes, and smiling Black women—all on a tablecloth-like patterned background, painted on canvas. Although one could read into this piece a happy history that never was, we can also detect a fundamental beauty, as well as the integral place of Black history in the American story. (Black history being as American as apple pie).

These collective stories, articulated pictorially through these pieces, approach the irreducible complexity of social and personal narratives. They are not simple, one-dimensional binarized narratives; like any authentic story, they offer the vicissitudes and complexities of experience.

Capturing the Historical Now: Listening Properly

Throughout their talk, what became clear as essential to Thomas and Helmreich was the recognition of the historical moment: the present. This recognition is only possible through the proper kind of listening. A listening that is absolutely active and responsive to the story being told. Accurate listening that captures a moment is crucial to archiving—this is what Helmreich told the audience was the purpose of an archive: A collection that truly listens to history. As Thomas said, this is what makes archives totally unlike “the first page of Google.”

This is what makes archives totally unlike “the first page of Google.”

Untitled, by Adrian Ghenie, captures the singularity of our historical moment:

It shows a person, distorted in a semi-repulsive manner, staring at their cellphone, which seems to vacate the painting’s subject of any vitality—they are alive without a life-force.

Though this is distinct from the other paintings mentioned so far, there is an underlying continuity. In a less literal way—meaning without direct reference to a specific historical moment—we find in this painting a true responsiveness to the malady of today. A lack, where something seems to be taken from us through our over-engagement with technology.

“Indicting the Audience”

Both Thomas and Helmreich were extremely cognizant of the place of the viewer in engaging with the documentarian pieces. Helmreich said that she was concerned with a non-critical attitude, promoted by social media use, which “monetized ignorance.” Thomas agreed, saying that he wanted to, at times, “indict the audience” and force a confrontation with truth.

While this may seem inherently antagonistic (and in a sense, it must be), we can also find an optimistic direction. Marinella Senator’s painting, Dance First Think Later, for instance, was a confrontation with the viewer, but one that offers hope.

The piece consists of anonymous hands reaching out, spread out across eight canvases, with text that says:

Social Media promotes a non-critical attitude, which “monetizes ignorance.”

“Light cannot only mean the old light. We need new light because of the exhaustion light suffers from the man’s misuses to which we submit it because of history’s severe darkness.”

There is something in the directness that implicates the viewer: It implores the viewer to recognize “history’s darkness”—but there was an explicit light gestured towards, both pictorially and textually. A hopeful reminder that history is still unfolding.